Hallucinating inaccurately

Part three: Clinical takeaways from The Experience Machine and predictive processing

What are the implications of predictive processing for psychiatry and clinical psychology? In my last two posts (Hallucinating accurately, part one; Hallucinating accurately, part two ) I located the theory in the history of ideas and explicated it as it pertains to perception. It’s time to see if these ideas apply to the healing professions. After a review of the basics and the potential that predictive processing has to explain psychopathology I will stick to discussing bread and butter concerns of clinicians, namely, therapeutic potential (usually in the form of the clinician “intervening on experiencing”) and the pitfalls that come with such “interventions”after persuading patients how their experience is constructed.

Experience may be constructed, but this fine philosophical notion comes close to saying “It’s all in your head. You are imagining things!”. When a clumsy clinician says that to their patient, it invalidates their experience. Not so good for the doctor-patient relationship. At the same time, it would be a shame to waste this liberating insight. It may be disorienting, but it has the potential to alleviate useless suffering. How should we communicate that hallucinated voices, pangs of self-hatred, obsessions about fatness, dread of speaking in public, or suspicions that the CIA has bugged your apartment may result from the brain’s balancing top-down priors against fresh sensory input?

Review: Who wins when senses clash with priors?

Before tackling psychopathology and clinical applications, let’s recap to make sure we’re all on the same page: Predictive processing is a theory of brain function that posits how the brain generates predictions about the world, compares them with incoming sensory information and updates mental models accordingly. This is all connected to the Free Energy Principle (FEP), an even grander framework positing that all biological systems, from single cells to brains, strive to minimize 'surprise' or 'free energy' by continuously refining internal models of the environment. So you can think of predictive processing as a special case of the FEP, applying it to the neurophysiology and computational work of the brain.

Let’s look now in more detail how predictive processing explains normal cognition, by breaking it down into five processes that the brain automatically implements as it infers the causes of sensory signals:

The brain maintains abiding, yet flexibly updated priors based on the statistical regularities of the world. These priors are activated “on demand” and issued “from above” as predictions.

These top-down predictions meet “bottom-up” sensory signals at populations of neurons that function as a comparator mechanism.

Predictions and sensory signals are then compared. Insofar as they don’t match, the comparator mechanism generates prediction errors that are sent up the brain’s processing hierarchy. (When sensory data matches predictions the job has been done; no “upstream” information flow is needed, so it is suppressed.)

Precision weighting adjusts the balance of these elements based on their reliability and significance.

Experience depends on the re-sculpted world model that results.

(Keep in mind that these simplified “ five-steps” describe one level of what in reality is a hierarchical cascade of iterative processes. Also, remember that we are limiting discussion to perception, while predictive processing has a lot to say about action and about the interoception of the body’s internal states).

Precision weighting is the weak link in the chain

Let’s focus on step four, the tricky process of precision weighting, because it turns out to be most relevant for psychopathology. Precision weighting acts like an umpire who makes calls under uncertainty; “he” adjudicates who wins. This is because sensory data may fail to conform to expectations if they are incorrect or because the incoming data are noisy or unreliable. Note well: the precision weighting of prediction errors is not assessed in isolation (as if the error signal had “something to say” on its own). Instead, it’s assessed in relation to the precision of both top-down predictions and bottom-up sensory data.

How is such weighting implemented “in the flesh”? Lest the metaphor of a human-like umpire lead us astray, let’s stick to Clark’s metaphor of precision weighting as a volume control that adjusts the synaptic gain applied to synapses in charge of processing error. Making prediction errors loud empowers them to revise predictions; conversely soft prediction errors give a pass to the status quo.

Let’s frame this as a story with a little drama. Imagine you’re driving down a foggy country road. Suddenly, a blurry red shape emerges ahead. You have never traveled this road before, so you lack past experience to generate a specific prediction. In the lingo of predictive processing, your priors concerning this red blur would merit low precision. At the same time, the fog is so thick that your visual input is riddled with meaningless light. This sensory information also doesn’t merit confidence and therefore it’s also assigned low precision (high uncertainty).

Unfortunately you are in a pickle: both predictions and verifications are poor. The relentless generation of prediction errors (“A barn? No wait, a billboard. No wait, a truck”) are all over the place, leaving you distressingly uncertain about what you are seeing and about what to do.

Ah! We’ve added distress to the drama. Apparently you are not a Tesla on Full Self-Driving mode, blithely computing inferences, but a being endowed with the capacity to suffer from uncertainty. Where does this suffering come from? Presumably, an unusually large amount of discrepancies (“errors”) in a potentially dangerous situation -speeding on a foggy road with a looming unknown object - increases the significance of the prediction errors, thereby ramping up their weight. Survival circuits involving the amygdala kick in, further amplifying the gain (weighting) of these prediction errors The result is a subjective mental state of anxious distress and hypervigilance.

This illustrates how precision weighting is not just about the reliability of information (that is, its precision, the inverse of uncertainty) but, importantly, also about its valence.

Riff: Precision weighting and the samsara trap

Let’s take a moment to riff on the significance of how valence mechanisms add “extra tinkering” to precision weighting. Information assigned high valence - good or bad -receives priority in processing, influencing perception. So much for “objective”, dispassionate inference, for impartiality, for attaining “the view from nowhere”. Precision weighting, in cahoots with valence, indexes all experience to the selfish viewpoint of the organism.

Permit me a high-flying speculation: is this not the very fountainhead of avidyā, the root cause of suffering in Buddhist philosophy? Or the Tibetan Lord Yama, chaining to the Wheel of Karma, like the roosters, pigs and snakes that it depicts as they bite each other, going round and round?

In some alternate universe where animals inferred the causes of sensation with equanimity, brains would only ask “What is?”. In this universe all experience is tinged with to answer the question “What is it to me?”.

In fairness to Lord Yama, animals like us wouldn't last a day in a universe where we only cared about inference. And let’s not pass the buck, because Lord Yama is us…

Aberrant precision weighting and the varieties of psychiatric experience

Having established the basics of predictive processing, let’s see what it has to say about psychopathology. The overarching notion is one of stupefying simplicity, that Karl Friston puts in the form of a sort of syllogism: If all of psychology corresponds to inference, it follows that all of psychopathology amounts to false inference.1 False inference arises from improperly calibrating the precision applied to predictions or to sensory data. This calibration, in turn, determines how prediction errors influence one’s world-model.

Beautifully simple or simplistic?

Theoretical simplicity can be beautifully elegant, but simplistic reduction only leads us to a dead-end street. Consider three varieties of misgivings regarding Friston’s sweeping statement: overreaching, invalidation, and biologizing.

First consider overreaching. Is it reasonable to posit one common pathway for all psychopathology? It certainly would be exciting to discover common mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders. But when applied to specific psychiatric disorders these hypotheses sometimes sound like facile re-description, replacing one jargon with another, as when they posit that anxiety disorders are due to excessive weighting of harm-related priors. (This kind of re-description is reminiscent of the purely theoretical, evidence-free adaptationist “just so stories” that are so tempting to come up with in evolutionary theory).

Let's unpack the issue of overreaching. We should note that discovering common mechanisms underlying disparate conditions happens all the time in general medicine. Think of how unrelated medical conditions have been linked to common factors such as inflammation or oxidative stress. Precedents like this suggest that searching for common mechanisms in psychopathology is not always overreaching nor a fool’s errand.

There is also a distinction to keep in mind before dismissing the notion of “all psychopathology amounts to false inference”. It only posits a common dysfunctional pathophysiology somewhere along a causal chain, but it does not say anything about etiology, that is, fundamental or originating causes. Etiologies could be as varied as you wish - genetic, traumatic, stress-related, developmental, inflammatory - anywhere along the bio-psycho-social spectrum.

On to the second type of concern, namely invalidation, that is, whether the theory reinforces a “Doctor always knows best” asymmetry between expert and patient. The notion that psychopathology amounts to false inference at first glance suggests that someone knows the truth, and someone else is mistaken:

Patient: “I’m experiencing X. ”

Doctor: “You are wrong! See, my theory proves it!”

The comeback to the doctor is that, of course, his/her experience is also constructed…

Despite the apparently all-or-nothing alternatives of true vs. false inference, proponents of predictive processing (including Clark) leave room for neurodivergent ways of being, as when Clark cites a study where “non clinical voice hearers” performed better than neurotypical experimental subjects when discerning speech masked by noise. At least as popularized by proponents, predictive processing does to some degree accommodate people who affirm “My brain is not broken” despite having classically described divergent, even psychotic experiences.

May I interject the point of view of a grizzled retired psychiatrist? Undoubtedly, some people are better off staying away from psychiatrists and managing creatively with whichever idiosyncratic world-interpreting equipment they were endowed. Check out, for example, websites for voice-hearers (Hearing Voices Network), and for people who affirm they live under persecution (Meetups for Targeted Individuals).

That being said, there is no way to ditch the concepts of dysfunction and disorder without inflicting a blind spot on oneself. There is something wrong when a teenage girl insists that she is fat despite a BMI of 15, when a retired schoolteacher has come to believe the Russians have bugged her kitchen, or when an 18 year old college student is tormented by voices mocking him wherever he goes. Notice that these are examples of are the easiest cases for a false inference take on psychopathology: hallucinations, dysmorphias, and idiosyncratic delusions.

Finally, one might think that predictive processing explanations of mental disorders, insofar as they are “brain-based” would perpetuate stigma the same way that "chemical imbalance" explanations of depression have done. Such explanations seemed attractive because they rendered moralistic shaming moot. But surprisingly, defective is no better than bad. Either way, the resonance between self-esteem and how one is esteemed takes a hit.

I think predictive processing explanations will fare better than “chemical imbalance” and other reductionist notions for two reasons. First, they align with adaptationist hypotheses of mental disorders, where dysfunction is on a continuum with function. Secondly is the notion that precision weighting is continuously variable - recall its analogy with a volume knob. Find the volume knob and adjust it. The suffering state may be excessive, mis-timed or stuck, but it’s still a "functional signal”.

All in all, I think it’s premature both to sign on the dotted line and to dismiss these theoretical proposals. They are works in progress, waiting for empirical neurobiological evidence. Within limits, the beauty of predictive coding remains in how it gets us to “first principles” in one fell swoop.

A master code that deciphers many texts

In an article relating the action of psychedelics to predictive processing and the free energy pinciple, Carhart-Harris and Friston don’t shy away from making “The Big Claim”, but now adding the mechanistic component of precision weighting:

“we take the position that most, if not all, expressions of mental illness can be traced to aberrations in the normal mechanisms of hierarchical predictive coding, particularly in the precision weighting of both high-level priors and prediction error.” 2

If this one-stop-shopping for a common mechanistic denominator pans out, it would be an amazing explanatory reduction. Here are some examples of how disruptions in precision weighting could account for four psychiatric/neurological disorders: 1) Chronic pain: Excessive precision weighting of pain predictions. 2) Anxiety disorders: Excessive precision weighting harm predictions. 3) Autism spectrum conditions: Excessive precision weighting of sensory inputs or low-level priors. 4) Prodromal (early) schizophrenia: Insufficient precision weighting of high-level priors coupled with excessive precision weighting of prediction error signals.

It’s worth noting that while most of these proposals are abstractly computational, when it comes to the last example (schizophrenia), the theory actually points to “wet-brain” neuroscience, locating aberrant neuromodulation within the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, also predicting that excessive weighting of prediction error explains the well-known phenomenon of aberrant salience - experiencing hum-drum situations as endowed with an uncanny significance that demands explanation.

Are there practical takeaways for the clinic?

Predictive processing is turning out to be a fertile field where a thousand theoretical flowers are blooming (undoubtedly alongside a thousand weeds). Good for theoretical neuroscience - but what about practical applications? It’s disappointing that, for now, applications are scanty, limited to “ interventions upon experience” - suggesting ways to engage with patients who suffer from conditions such as chronic pain, functional paralyses and perhaps also anxiety and mild depression.

Despite these limited practical applications , I’ll bet that theoretical advancements will yield benefits in the future. We need to explore, test, try things out…. For example, I suggest below a modification of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as a“toy model” to explore the potential of the theory , first for CBT and perhaps for psychodynamic therapy in the distant future.

Rant: The pitfalls of positive affirmations

Before I disclose my toy model, would you indulge me ranting about a supposed “practical application” of predictive processing that Clark alludes to? This is the self-help practice of repeating “positive” statements about one’s worth or efficacy. My eyebrows shot up when I read Clark endorsing the effectiveness of affirmations. Presumably, repeating self-assured “positive” statements about oneself establishes priors (predictions) that promote enhanced self-esteem and mastery.

I confess that I have an aversion to telling myself what to tell myself. Rah-rah locker room pep talks energize the team, but cheering your reflection in a mirror does not. Stuart Smalley is fooling himself repeating "I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and doggone it, people like me! "

Affirmations, as merely free-floating words, should not be trusted. Our left hemisphere language network is quite adept at playing prosecuting attorney and defense attorney, and it can turn on you on a dime. That’s why I’m wary of intoning “You’ll will get an A on the exam! You are so talented, you are brilliant !” - because the next minute I may hear “You will fail! You’re an impostor, you’re a failure!” Don’t believe the hype, be it “positive” or “negative”. As the 1972 French song says. it’s all paroles, paroles, words, words…

I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and doggone it, people like me!

To be fair to psychotherapists who recommend positive affirmations, l will say they specify that affirmations should be tailored to individuals, aim at specific achievable goals and be limited to amplifying conscious “core values”. And yes, there is some evidence supporting optimistic autosuggestions and positive affirmations. All the same, I’d love to see replications and a rigorous meta analysis of the existing studies. (Nothing motivates the search for contrary evidence like a gripe…)

Well, enough of my rant…

Honest placebos: No need to lie

Healers of all types have, of course, “intervened upon experience” since time immemorial, unknowingly making use of predictive processing. I’m referring to the placebo effect, a phenomenon that provides clear evidence that “interventions upon experience” can influence medical outcomes. In modern times, traditional placebos have typically consisted of “sugar pills” or fake interventions imbued with healing power by an authoritative healer, institution or ritual. Placebos have shown efficacy for various conditions, including psychiatric disorders (interestingly, with varying degrees of success across different conditions.3 ) And placebos work even for animals! 4

Earlier, I criticized “positive affirmations” for their reliance on mere verbalization. Does this undermine the rationale for the placebo effect, which one might assume depends on the prescriber's mere words? No, because placebos work regardless of any expressed rationale, suggesting that the effect relies on deeper priors than the mere rationalizations uttered by the doctor. That this is so is exemplified by the honest placebo effect. When prescribing an honest placebo, patients are explicitly told they are receiving an inert substance: “This placebo pill may help; it’s an inert pill without physiological effect”. Studies, such as one on open-label placebo injections for chronic back pain, have corroborated this phenomenon (see Open-Label Placebo Injection for Chronic Back Pain With Functional Neuroimaging A Randomized Clinical Trial ) 5

What does this tell us? The placebo effect in general teaches: prediction impacts experience; the honest placebo effect teaches: the placebo mechanism depends upon deep priors and contexts - statistical patterns in situations, not on language.

A toy model demonstrating constructed experience

So, the theoretical promise of predictive processing is great, but the clinical applications are few and tricky to implement. How to move ahead? We need to run thought experiments, construct toy models of how predictive processing could be applied concretely. I like to think that, as predictive processing notions will continue to shape therapist’s understanding of how the mind works, the ideas will be applied to all sorts of therapy, including psychodynamic therapies, where the work has to do with shaping habitual, entrenched patterns of interpreting and behaving. But to start, it’s more tractable to consider a toy model involving manualized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

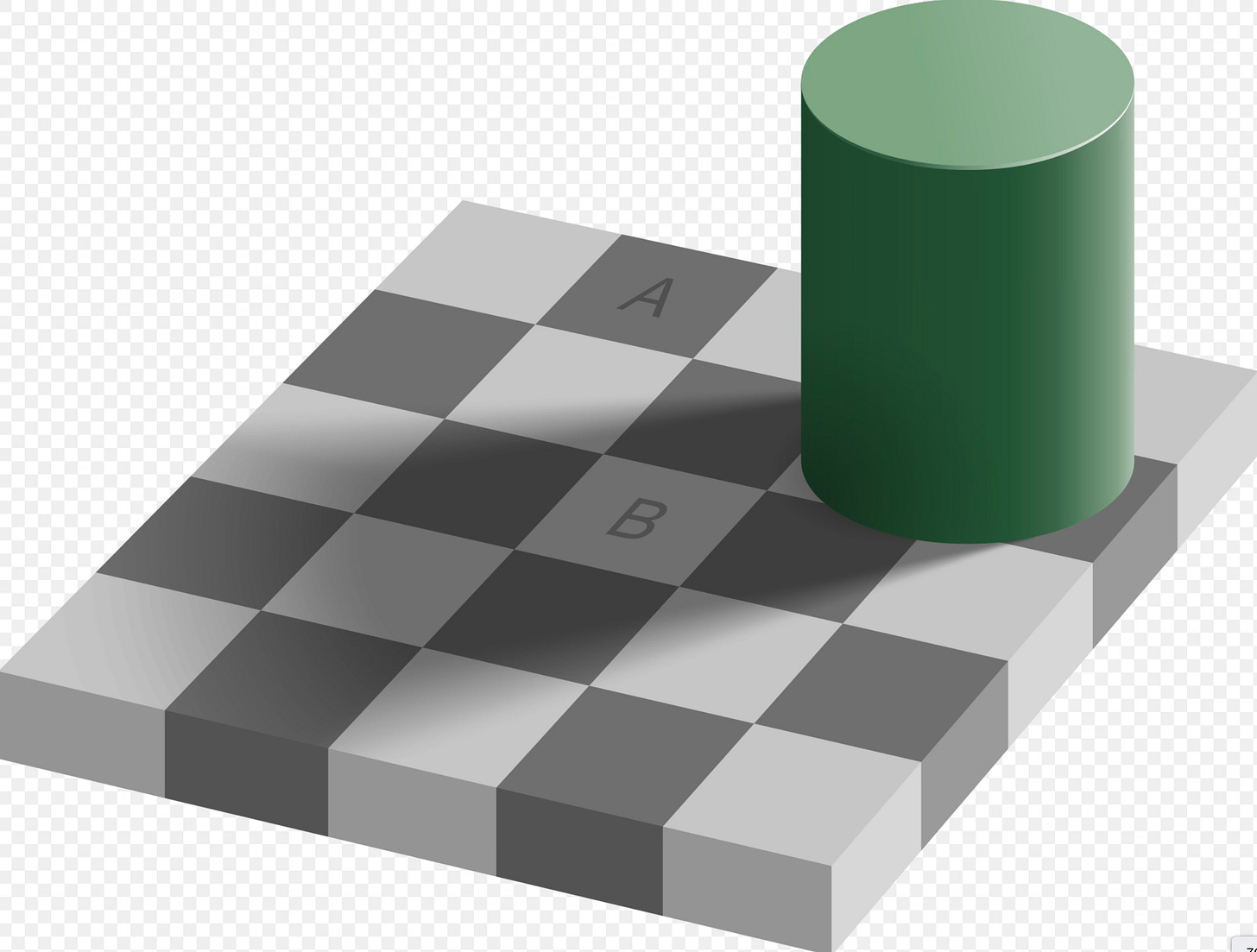

The toy model thought experiment goes as follows: Incorporate live demonstrations of constructed experience into CBT. The idea is to capitalize on how illusions demonstrate the constructed nature of experience. After a psychoeducational preamble, the therapist guides the patient through vivid demonstrations of how perception is constructed. We start with visual illusions because the elaborate constructs concerning self and others, ensconced high up in the brain’s hierarchy and protected with rationalizations are impossible to demonstrate.

Many visual, auditory or tactile illusions would be appropriate, although auditory illusions (for example the McGurk effect), or tactile illusions (for example the “Rubber Hand Illusion”) are rather cumbersome to integrate into psychotherapy. For our toy example, let’s stick to visual illusions (a wonderful resource is The Illusions Index website from the University of Glasgow: The Illusions Index ) Not all visual illusions are apt, only those that illustrate how perception is influenced by context, namely, context-dependent visual illusions (my favorite example is shown below).

Many patients will have experienced these illusions and dismissed them as curiosities The difference is that now the therapist links the disconnection between what-seems-so and what-is-so with the constructed nature of experience. Dwelling on and savoring the right-before-your-eyes mismatch works like a micro-psychedelic trip that loosens the grip of established priors.

As perceptual illusions unsettle the precision weighting of sensory priors, the therapist capitalizes on this and urges a a new perspective. Eventually, the hope is that such insights, with psychotherapeutic guidance, will generalize beyond sensory illusions to the constructed nature of automatic thoughts, phobias, narcissistic rage, irrational jealousy, transference distortions, etc - the targets of psychotherapy.

Yes, “believing is seeing”. Here’s the uncanny Adelson’s checker shadow illusion ( also illustrated in an earlier post):

The psycho-educational preamble to these shaking-up exercises might run something like this:

“Our brain makes sense of the world based on past experience. From the moment we are born our brain learns how the world hangs together and takes note of it,, so it doesn’t have to figure out from scratch everything it runs into. It’s more efficient to make predictions, or take guesses about the way things are, and adjust the guess if necessary.

But sometimes the brain fails to adjust its guesses because of habit. When it sticks to outdated guesses, we experience (dysfunctional anxiety, dysfunctional depressed mood, dysfunctional suspiciousness, dysfunctional shame, etc).

Once we understand how this works, we may be able to watch the automatic process as it happens, and become less attached to those first guesses, allowing us to make fresh interpretations of the world around us”.

Notice that this explanation communicates in so many words that the trouble is being “out of tune”, not being “broken”. It de-emphasizes disorders and defects. The emphasis on “tuning” is consonant with (accidental pun…) the “computational goal” of tuning the gain on precision errors. No need to re-string the piano or rewire the synapses, just tune the instrument.

Raising up our self-observing homunculus

Why would vividly experiencing and savoring illusions facilitate psychological change? There are two reasons. First, the already mentioned “micro-hallucinogenic” effect loosens priors and facilitates understanding the world anew. Secondly, having such an “experience of the arbitrariness of experience” is, as it were, a meta-experience of the “inner observer”. I like to think of the inner observer as a construction in itself, a homunculus that arises de novo when properly invoked.

The concept of therapeutic dis-identification isn’t new; helping patients distance themselves from their automatic priors has long been an implicit part of CBT. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) takes this a step further with its principles of “cognitive defusion”, which encourages individuals to “de-fuse” from maladaptive thoughts and feelings. This implicitly invokes what I termed “the homunculus”, a self-observing agent that has its own experience.

In the toy model, one pairs predictive coding concepts such as the psychoeducational “blurb” quoted above with guided, deliberate, sustained attention to experiencing illusions. So there are two modes of action: the “micro-psychedelic” effect of loosening priors, and the dis-identification or self-observation from a “de-fused” stance.

So much for a modest proposal for weaving the insights of constructed experience into CBT. Again, a grander perspective would envision applications for any psychotherapy that goes beyond support, even psychodynamic therapies. It would be comical, today, to incorporate exercises in visual illusions to psychotherapies for interpersonal dysfunction or disorders of the self, but the grand liberating insight of the constructed nature of experience still applies. What are transference distortions if not recalcitrant priors about self and others? Come on, psychoanalysts and theoreticians of clinical psychology, theorize the potential, invent new techniques!

The upshot and an afterword: Bach intervening on experience

To recap: Explaining the constructed nature of experience may occasionally alleviate anxiety, depression, hallucinations or delusions. However this is tricky and requires careful handling to preserve the healer-patient relationship. The self-help practice of positive affirmations is questionable. The use of illusions, savored and amplified as “micro-psychedelics experiences” could be incorporated into manualized CBT for select conditions. We leave it to psychodynamic psychotherapists to explore the grand vision of integrating the insights of predictive processing into their work.

And we close with a look to the past. After all, there have been ways to instill priors that alleviate suffering since time immemorial- the trove of verbal, artistic and ritual positive prediction in all religions:

"He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away." (Revelation 21:4).

Karl Marx memorably called religious consolation "the opiate of the masses," "das Opium des Volkes." Over time this evolved to suggest that the very essence of religion was oppression and pacification. But Marx’s point refracts into different hues of meaning when quoted in context:

"Die Religion ist der Seufzer der bedrängten Kreatur, das Gemüt einer herzlosen Welt, wie sie der Geist geistloser Zustände ist. Sie ist das Opium des Volkes."

"Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people."

It may be that the “opiate of the people” affects the same brain areas that the opiate from the poppies affects. Suggesting that this is so, Clark cites a study that compared the pain experienced by Catholics presented with religious images with the pain experienced by “avowed atheists and agnostics”. It showed that religious beliefs ameliorated physical suffering. The findings were corroborated by fMRIs: An fMRI study measuring analgesia enhanced by religion as a belief system.

So let’s sweeten the end with religious consolation, an aria from the Easter Oratorio BWV 249, by Johann Sebastian Bach. Its refrain is a prediction, Gentle shall be my death-throes be (Sanfte soll mein Todeskummer ), sung by the tenor. Such an explicit prediction may seem “merely” verbal, but it is melodious and gets the deeper brain reverberating harmoniously.

This performance posted on YouTube is my favorite. The tenor (Mark Padmore) sings with a childlike simplicity that’s just what the aria calls for (nothing would be worse than singing this aria with a stilted operatic voice! ) The strings and recorders envelop us in folds and folds of music, echoing the lyric referring to a shroud. Somehow the ghoulish potential of death-throes and shrouds is turned into being cradled by eternity. The heart of a heartless world indeed!

For those who don’t have faith in a heavenly, fatherly God, no worries - the aria works its magic all the same. It’s an honest placebo - no belief in verbal propositions necessary. Within certain boundaries, there are states of the world that become what they are because of what we are prepared to make of them. When Bach hacks predictive processing, music is all you need to predict gentle death, a fine hallucination to make accurate.

Sanfte soll mein Todeskummer. The aria ends on time stamp 7:16. The refrain, “Gentle shall my death-throes be” appears in the Italian subtitles as Dolce sarà il mio dolore di morte.

"Synaptopathy and the Bayesian Brain with Karl Friston | WIRED Health" [Video]. YouTube.

Carhart-Harris RL, Friston KJ. REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2019 Jul;71(3):316-344. doi: 10.1124/pr.118.017160. PMID: 31221820; PMCID: PMC6588209.

Bschor T, Nagel L, Unger J, Schwarzer G, Baethge C. Differential Outcomes of Placebo Treatment Across 9 Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024 Aug 1;81(8):757-768. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0994. PMID: 38809560; PMCID: PMC11137661.

Ashar YK, Sun M, Knight K, et al. Open-Label Placebo Injection for Chronic Back Pain With Functional Neuroimaging: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(9):e2432427. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.32427