Psychiatrists who don’t know what mood is

A theoretical article goes to the foundation - the rock bottom - of mood

That would be me, or at least, that's how I felt before I read "The Evolutionary Origin of Mood and Its Disorders”. Even after studying this article, my professional comprehension of "mood" has only marginally progressed beyond our everyday folk psychology.

Still, I gained a sense of what the foundation of mood might be. Throughout most of my career I did not have a sense of this foundation. Early on in psychiatry training, I learned that I was supposed to treat mood disorders. Just make people feel better, apparently. But I was supposed to make people feel better without understanding what mood was supposed to do. Did it have a function? Had I become a cardiologist treating a patient in heart failure, I would have known that to treat the patient’s symptoms I should intervene to improve the pumping function of their heart. But what were all those brain mechanisms that regulate mood - speculative, barely understood mechanisms- supposed to do?

As mental health clinicians we grapple with our lack of understanding of functional significance of mood. When do normal responses transform into conditions that should be deemed pathological, warranting a medical perspective?` If someone suffering from a major depressive episode or a manic episode has a “broken mood”, what is their well-functioning mood supposed to do ?

The very definition of some disorders is telling, for example, the DSM 5 TR definition of the quintessential, most discussed, most prevalent mood disorder, a Major Depressive Episode. Its criteria include “Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day (by subjective report or observation of others”. Note the circularity evident in how “depressed mood” appears as part of the definition of ... depression. This circularity apparently bothers no one. Why? Perhaps because we understand that the “depressed mood” in the definition pertains to a subjective experience, which, like other subjective experiences cannot be further defined. Like defining what it’s like to see the color red. But could there be a more precise, measurable specification of what “depressed mood” is that does not rely on subjective experience?

Now, I have discovered that opinions vary about how sound “The Evolution of Mood and Its Disorders” is, as I learned from a scholarly colleague who found it full of holes and circularities. I may discuss his critique once I have parried it for a bit. I still hold that “The Evolution of Mood and Its Disorders” is a fine theoretical article. It posits a deep phylogeny to mood as a basic modulator of animal behavior, basing the fuzzy concept of mood on rock-bottom behavioral concepts of reward and punishment and on engineering principles of signal detection. Finally, it proposes a scientific definition of mood that applies across species, making the phenomenon of mood an ontological natural kind. Speaking loosely, mood is deeper than emotion.

Watch out – reductionism ahead!

Dear reader, clinicians whom society has entrusted with the awesome charge of alleviating the suffering of moods, why is it worth your time to read this article when it takes you so far from clinical matters, all the way to animal behavior? Precisely because it brings us to first principles, to the very foundation of mood. What is mood and why is it the way it is? Well, “Everything is the way it is because it got that way that way”. [i]

But a word of caution. If you sympathize with this approach, you may be branded as a reductionist. I have developed a thin skin when it comes to such accusations after reading psychiatrist/philosopher Ian McGilchrist’s The Matter With Things, a voluminous magnum opus that argues for holism, top-down causation, interdependence, and the workings of teleology in nature. Whereas I relish every explanatory reduction I meet. For me, explanatory reductions do not subtract from the wonder of Being. Matter is holy, matter is mater nostra...But! Let’s not get lost in metaphysics, back to the article!

A scientific definition of “mood” need not encompass its conscious experience. That may sound paradoxical but consider the phenomenon of blindsight. In the case of blindsight, it’s demonstrable that the visual system of a human subject can modify his or her behavior – for example, to avoid a threatening visual stimulus– while not consciously seeing. In the bare-bones account of the foundation of mood here in question we should not expect subjective particulars of human mood, although two fundamental features we can vividly experience – the cognitive biases of mood states. We will only arrive at a rough definition that does not address most of human experience, but using it we’ll be able to trace the way that mood variation affects our tendencies to interpret and respond to the world. And it’s precisely the simplicity of a foundational definition that may clarify conceptual muddles in psychiatric nosology and affective neuroscience.

The viewpoint from Behavioral Biology: How do animals fine-tune their behavior?

The authors of this paper are behavioral ecologists, so they are fundamentally interested in the adaptive functions of animal behavior. In other words, they are not primarily interested in mechanisms, such as neural circuits or neurotransmitters. And they are not clinicians, so they are also not primarily interested in clinical utility, although they suggest that their approach “may provide some insights...of use to researchers with more mechanistic and therapeutic goals”.

Their framework draws inspiration from a diverse array of ideas:

They embrace the concept that emotions represent the activity of survival circuits. Notably, the authors draw upon Joseph LeDoux's proposal to refine emotion terminology in basic neuroscience, again, replacing talking about emotions like “fear” with the notion of the activity of survival circuits.

They incorporate the dimensional classification of emotions. This entails theories that aim to organize emotions and their fundamental components by plotting them on a two-dimensional (or more-dimensional) space. Most often, these dimensions have been valence and arousal (although in this paper, the dimensions will represent something else altogether).

They integrate signal detection approaches to emotion, taking us into the realms of engineering and information theory.

They experimentally ground their theory on the cognitive bias literature, which suggests inferring mood-like states from the behavior of animals based on how they interpret and respond to ambiguous situations.

Their framework also draws upon traditional behavioral ecology, seeking to understand how an animal's physical condition, including factors like health, nutrition and overall well-being, influence their behavioral choices.

It is remarkable how this theory manages to synthesize insights from such a wide array of fields. Two cheers for integrative thinking and the consilience of the sciences!

We must admit that the article stops short of saying much about the evolution of mood disorders as such. We’ll get to that near the end of this post. But a paucity of explanations about the evolution of disorders makes sense. As Randolph Nesse has said, evolutionary hypotheses should not be shoehorned into explaining dysfunctions, only the vulnerability to dysfunctions.

Emotions and Signal Detection Engineering

We immediately side-step the debates surrounding “constructed” vs. "deep primitive circuit" concepts of emotion. In this paper, the interpretation of "emotion" aligns with Joseph LeDoux's definition as the outcome of survival circuits: "...cognitive, motivational, and physiological changes triggered by the appraisal of environmental situations," which serve to "allocate and marshal the individual's cognitive and behavioral resources toward the most immediately crucial, fitness-relevant priorities given the current state of the world."

What about what’s ultimately important for us, the “subjective valence” of emotion? The multilayered complex blends of our emotional experience? All this is not our concern for now. Remember, we are starting at the foundation of the building, whereas we live in the penthouse. We are to think of basic emotions as signal detectors. Detectors of what? Of situations relevant to fitness.

In general, detectors are entities rigged in in such a way that some change in the world functions as an input that triggers generating an output. When it comes to emotions, the outputs are cognitive, physiological, and motivational changes that are adaptive for dealing with, or capitalizing on the change or situation that initiated the input.

So basic emotions simply detect and respond in real time. Notice, in real time, because as we’ll see, the logic of mood as opposed to emotion depends precisely on time – what the future may bring.

Now here’s a challenge for all detectors: Our brains do not have some kind of direct “plug-in” to states-of-affairs in the world. We must make do interpreting noisy information, to arrive at an interpreted, constructed meaning that is always uncertain. What-we-make-of-things is only probabilistically associated with “what’s-really-out-there”.

Let's examine a few examples to illustrate this point: A rustling noise in the forest could either signal a predator's presence or simply be the result of the wind rustling the leaves. A patch of red on the far side of a green valley may indicate ripe berries, or it could be a cluster of autumnal leaves. When your friend passes you without acknowledging you, it might mean she is intentionally ignoring you, but it's equally possible she was deeply engrossed in her thoughts. Similarly, when a friendly barista flashes a smile, it could be interpreted as flirting, or he might simply be performing his job with courtesy. In another scenario, when your significant other takes forever to respond to your messages, it could be a sign of impending ghosting, or it could merely be due to a busy schedule.

However, decisions on how to react must be made, even in the face of uncertainty, because not responding is, in itself, a form of response.

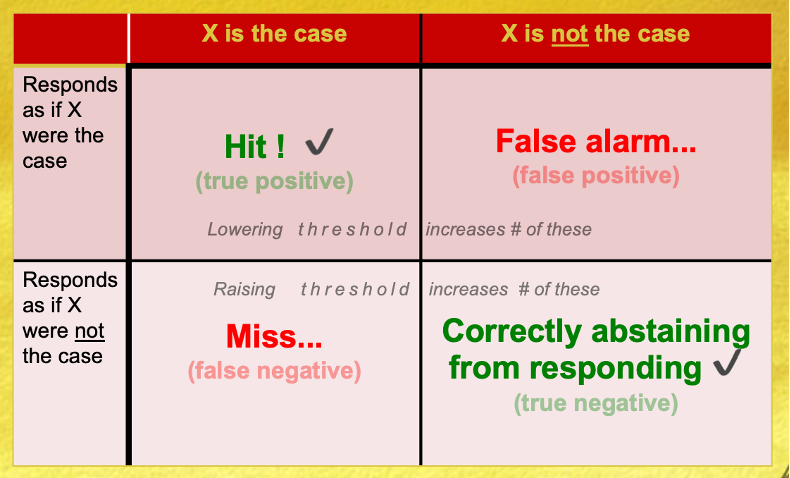

Imagine you are counting on a detector to protect you from fire spreading out of control in your kitchen. Whatever it does or fails to do falls into the four conditions of signal detection decisions: true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives.

Now, remember that the input is inherently noisy. For instance, the detector might generate an output, such as a fire alarm sound, immediately after burning your toast. The sensitivity of detectors becomes a critical factor—how "trigger-happy" should they be when confronted with uncertainty? What level of sensitivity is ideal to detect "fire," and how cautious or restrained should they be to prevent unnecessary alarms? These sensitivity levels are referred to as detection thresholds, and they affect the balance between what we want (true positives and true negatives) and what we don’t want (false positives and false negatives).

It can be a bit challenging to keep these concepts clear, so let's break down the effects of tinkering with detection thresholds:

- Lowering detection thresholds increases the number of true positives.

- Raising detection thresholds increases the number of true negatives.

That’s all great, but unfortunately, this also happens:

- Lowering detection thresholds increases the number of false positives.

- Raising detection thresholds increases the number off false negatives

We are stuck by the very structure of reality with the tradeoffs of signal detection. Any behavioral gizmo that tries to make its way in the world , be it an animal, a robot, a self-driving car or a Martian rover, must balance false alarms with failures to act.

We can’t help settling on a compromise – but what is the optimal compromise? How should one determine optimal detection thresholds? Well, that hinges on the significance of the decisions to trigger or refrain from triggering the alarm – the value of the decisions. For instance, is it crucial to activate the alarm under any circumstances, even if that means occasionally sounding a false alarm? Conversely, does dealing with frequent false alarms come at a high cost, prove bothersome, or have other counterproductive consequences? These considerations will guide the threshold settings.

From smoke detectors to how animals should set optimal detection thresholds

Having made the analogy of emotions to detectors whose detection thresholds are important to adjust, what are moods? In the folk and clinical usage of the term, moods are understood as affective states that last longer than emotions. It seems that moods are...preparing for the future... In this framework, we interpret moods as adjustments of detection thresholds. But on what criteria should these thresholds be adjusted?

It turns out that today’s world predicts tomorrow’s (more on that below), so the optimal detection threshold should take into account “how things have been going”. That is, the frequency of rewards and punishments and the condition of the organism should be integrated over time. Organisms experiencing repeated punishments then lower the detection threshold for anticipating and reacting to punishment. This amounts to anxious mood, a persisting affective state of increased vigilance and readiness to flee. Conversely, organisms experiencing repeated rewards (especially unexpected rewards) lower thedetection threshold for expecting and pursuing rewards. This amounts to an elevated mood, a persistent affective state that fosters an optimistic cognitive bias and inclines the organism to pursue potential rewards.

Cognitive biases are tendencies to interpret ambiguous situations optimistically vs. pessimistically. Let’s bring the abstract notion into our lived experience. Imagine being invited to a party by a new acquaintance, shortly after relocating to a new city. A party! An ambiguous situation full of potential rewards, but also failures. Imagine how you interpret the ambiguity of the prospect and your decision to act depending on your mood, depressed, or upbeat. You are experiencing your mood-dependent adjustment of detection threshold for possible reward, in action.

Now notice we have discussed two thresholds to “set”, namely thresholds to detect/respond to punishment and threshold to detect/respond to reward.

Two independent variables cry out for plotting on x and y axes – so let’s do so:

A definition of “mood” that applies from bugs to humans

We finally arrive at a definition of moods:

“Moods are relatively enduring states that arise when negative or positive experience in one context or time period adjusts the individual’s threshold for responding to potentially negative or positive events in subsequent contexts or time periods.”

Unlike emotions, moods are detached from immediate triggering stimuli –their proximate causes are the output of an integrative function of the organism’s emotional experiences over time. Moods “spill over” emotional states beyond current events or context. [i] And notice that moods – or “precursors of mood-like states”, if you will – apply “across taxa”.

Now, is it merely a theoretical fantasy that cognitive biases could apply “across taxa” (that is, to a wide range of extremely dissimilar animals)? Check out this delightful article:

“Agitated Honeybees Exhibit Pessimistic Cognitive Biases”, by Bateson et al

https://www.cell.com/fulltext/S0960-9822(11)00544-6

Moods are bets that the “here and now ” will apply to the “then and there”

Emotions detect and respond; moods integrate to prepare. But we still haven’t answered the central adaptationist question: What’s the point- the functional payoff- of such “integrating”? Of affectivity “spilling over” from the present to the future?

It has to do with the fact that “the world is generally autocorrelated.”

Here’s an idea so extremely simple that it’s extremely deep: the world is generally autocorrelated. It sounds like an oracular snippet pronounced by Heraclitus. It’s a “first principle” of the universe that we don’t notice, because it’s taken for granted as an all-encompassing “prior”. Just like the proverbial fish that don’t notice they are wet. The autocorrelation of the world turns out to be the key theoretical reasons why animals have mood systems.

What does this autocorrelation mean? That states of affairs in the world do not arise randomly without relation to prior states. Therefore, “bad times” and “good times” tend to last, punishments clump together and rewards clump together. This does not mean anything fancier than... situations last, so today’s world predicts tomorrow’s. (Of course, change eventually comes, but the principle of autocorrelation, statistically, holds).

So, let’s now understand why the unconscious, foundational trick of mood – namely, adjusted detection thresholds that bias judgment and behavior concerning the future - make adaptive sense. Why the complication of having affective states last, and not just evaluate each situation afresh? Because we’d be wasting the information that the world’s autocorrelation provides. Instead, our affective system exploits this information by setting detection thresholds accordingly – to optimally allocate effort. Were we equipped only with short-lived emotions, and not sustained predictive moods, we’d be flying blind.

Not only is the “world-out-there” autocorrelated, the physical condition of the organism is autocorrelated. If you are lame today, it’s likely you’ll be lame tomorrow. Now, the physical condition of the organism is not relevant to the probability of rewards and punishments “out there”, but it does affect the value (costs vs. profits) of signal detection decisions. For example, not sounding the alarm about a predator – a false negative - is costlier if you are lame and hobbled in your ability to escape. False positives are also costly if you are in bad shape, because they have you waste energy that you can’t afford to waste chasing after mirages.

Notice the consequences of physical infirmity: Individuals are both less able to cope with threats and less able to afford wasting energy on potential failures. From a psychological perspective one would predict that being ill, malnourished or lame would shift the detection thresholds for both axes, making animals both anxious and depressed.

Now consider, what counts as “the condition of the organism” for humans? Certainly, physical condition is important, but our fitness-relevant “condition” encompasses our social condition. Social condition – status, alliances, belonging, attachments - also “autocorrelate”. If your social status has declined and you are shunned today, it’s likely that you will continue to experience a low social status and be shunned tomorrow. And the bright converse of this applies as well, of course. Thus, the autocorrelation of our social condition further underscores the logic of adjusting detection thresholds. In other words, it’s a key determinant of mood.

Implications for mood disorders

This theory has primarily focused on understanding normal mood variation, contending that it’s a phenomenon that applies “across taxa” and serves the adaptive function of modulating behavior by predictively biasing the detection thresholds for states of the world relevant to fitness. But how does this framework relate to mood disorders?

This framework aligns with the implications of all evolutionary hypotheses that attempt to explain depressed or anxious moods. For instance, “...key features of moods, the anhedonia, pessimism and fatigue in depression, and the vigilance, threat-bias and physiological response of anxiety, represent means by which they fulfill their evolved function”.

But evolved functions can malfunction. For example, analogously to the contrast between normal inflammation as a defense and how it goes awry and become an inflammatory disorder. So too are non-disordered depressed or anxious moods defenses that can become depressive or anxiety disorders. It is no surprise that depressive and anxiety disorders are often triggered by life events, and that it is difficult to find some non-arbitrary boundary between normality and disorder. Thus, the key implication of this framework and other evolutionary hypotheses is that“...what we currently diagnose as disordered mood represents a mixture of cases where individuals have had adverse life experiences, but their mood system is itself functioning exactly as it should”. It follows that if we are indeed lumping normally functioning moods and dysfunctional moods when we study mood “disorders” – especially depressive – it is difficult to discover medications whose benefit robustly separates from that of placebos. And that it’s difficult to find what are the “key ingredients” of manualized psychotherapies if they don’t consider the idiosyncratic physical condition and social condition of the patient.

In The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow Into Depressive Disorder, Horwitz and Wakefield proposed re-embracing the traditional notion that mood changes resulting from life events do not necessarily indicate a disorder. Of course, it’s understood by all reasonable clinicians that this is the case, and our diagnostic manual does acknowledge this to some extent. However, the suggested revival would go beyond this acknowledgment. Here's the reference, which, despite having a title that sounds like tiresome anti-psychiatry, offers a well-reasoned and balanced perspective:

The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow Into Depressive Disorder Horwitz, A. V., & Wakefield, J. C. (2007).Oxford University Press.

Link (APA PsycNet citation): http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2007-05332-000

Finally, another implication pertains to the essential diagnostic criteria that should define conditions as depressive or anxiety-related in the first place. According to this "foundation of mood" perspective, we should elevate cognitive biases related to predicting and interpreting potential rewards and punishments to necessary criteria. In the context of depression, for instance, this would manifest as a pessimistic cognitive bias concerning future potential rewards. These biases may be equivalent to Beck’s “Cognitive Triad” of depressive distortions, but here they are elevated to the status of being essential in the definition of depression.One might also argue that, for socially obligate beings like us, these biases extend to estimating the capabilities, efficacy and worth of the self.

Venturing deeper into the theoretical underpinnings of these subtleties would lead us beyond the confines of "the foundation of mood" and into the realm of its more recent phylogeny. The building has a foundation, but we are living in its penthouse. As the saying goes, "Everything is the way it is because it got that way." – and it became that way little by little over the eons. Perhaps in future discussions, we'll explore the intriguing latter evolution that shaped mood into what it is today...

Takeaways:

1. Emotion functions to detect and respond.

2. Mood functions to integrate, predict, and prepare.

3. Mood reflects the ongoing momentum – the autocorrelation - of the world.

[i] This definition excludes what is commonly referred to as "momentary mood." Momentary mood fluctuations are not influenced by an integration of how well or poorly things have been progressing over a period but rather by how they momentarily deviate from expectations. This deviation is contingent on a "prediction error" or, in calculus terms, the "rate of change" of rewards and punishments, as opposed to their absolute values.

[i] Attributed to turn of the 20th century biologist D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson

Thanks a lot for writing this!!! I particularly look forward to instalment on similar topics on this Substack. The way you write makes it easy to understand the concepts and their real world implications. I'm sure more primary source materials would quickly exhaust me.

Wow and bravo— thank you!! I am a psychiatrist, practicing for 20+ years now. And I have an amateurs interest (and “mastery”) of philosophy. I LOVE this stuff!

The distinction between mood and affect has for DECADES now been an irritant to me, being unable, as I have, to posit a definition much beyond “affect sustained over time” (or some such similar, pure, unalloyed hand-wavium) as the best I could do.

Which is a definition almost immediately given lie to by the very existence of “Behavioral Activation” as an empirically validated therapy. And one which is satisfying to literally no one.

I have taken a small (as in, Planck-scale sized) amount of comfort in reading a recent book by Sean Carrol on quantum physics, and learning that the basics of that discipline (I.e., the Schrödinger wave function equation) were laid down in, literally, 1926. ….and yet no progress to speak of has been made in what quantum physics actually MEANS. (“Many-worlds” theory? The Copenhagen interpretation?) Which is a big part of why no one really seems to actually “understand” it.

The basic MATH is well understood, and that math can make scary-accurate predictions down to 1.2731 ga-zillion decimal places — and this has been true for almost 100 years now. But what does this math actually MEAN?

So, on one level (mathematically) quantum physics is about as mature as a science can be. At the level of theory, it apparently still needs a lot of work.

Psychiatry and psychology are even less mature than this. Scientifically, explanatorily, predictively, and philosophically. QM is probably an unfair comparison from the get-go, and I am just free-associating a bit too much. It’s just what comes to mind.

But I am hopeful that predictive processing models have, maybe, the potential to begin to rectify portions of the unholy mess of modern psychiatry, though I am hesitant to get my hopes up for a psychological Theory of Everything— much less anything *mathematically* predictive, precise, and accurate.

Maybe I’ll start a substack and call it Schrödinger’s Mood.

Anyway, sorry for the word salad. Thank you for this!!